The planet Mars has captivated humanity for millennia. Perhaps the most striking pinprick of light in a vast, dazzling night sky, humans have gazed upon it in wonder at its distinctive, unique red glow- as it stands out as a beacon of colour in an otherwise black and white sky. The earliest known name for our second nearest planetary neighbour- Har Decher- meaning ‘the red one’ in Ancient Egypt- perhaps signifies the exceptional specialness of the far out world. The planet eventually was given its name by the Romans, who named it Mars after their God of war. They perhaps got the idea off the Greeks, who also named it after their own God of war- Ares. Even in a sky in which stars and planets alike, when viewed with the naked eye, twinkle as their light is distorted and scattered by the Earth’s thick atmosphere, Mars’ distinctive reddish glow remains obvious and striking.

It is no wonder, therefore, that the human fascination and interest in Mars has transcended millennia, centuries and various levels of technological and philosophical advancements. No matter how far we’ve come as a species, our intrigue in the red planet has never wavered. Even though it is not our closest planetary neighbour in an endlessly vast and expanding universe- Venus, and even at times the scorched planet of Mercury are closer- Mars has long been touted as Earth’s twin. A similar, if desolate, sibling of our rich, diverse, bustling home world, situated across 193,000,000 miles of void. (although this varies as both planets go about their vast orbital journey). A dark planet; Mars receives around 40% of the sunlight the Earth receives, and the sun appears about 5/8 the angular diameter it does on our home planet. One of the most amazing features on Mars is the dormant Volcano- Olympus Mons. The tallest known volcano in the entire solar system, around three times the hight of mount Everest and roughly the size of France- if you were to stand on the mountain, it would be impossible to tell you were on a mountain, as the vastness of Olympus Mons means that it would stretch far beyond the visible horizon, akin to standing in the centre of France you wouldn’t be able to see the white cliffs of Dover, the beauty of the Swiss Alps, the Pyrenees on the Spanish border nor the glistening blue waters of the Bay of Biscay.

Whilst it’d maintained interest for countless years, from countless civilisations, the first ‘modern’ scientific observations of the red planet weren’t made until the early 1600s- primarily in Europe. German astronomer and mathematician Johannes Kepler (1571 – 1630) first theorised in 1609 in his writings named Astronomia Nova that Mars orbited, as per his first two laws of planetary motion, in an elliptical orbit. This was largely at odds with teachings at the time that maintained that Mars, along with all the other known planets, went through a perfectly circular orbit. Whilst we now know that Kepler’s findings were effectively correct, planets do generally orbit in a pattern akin to an ellipse due to their mass and kinetic energy- this was considered a relatively revolutionary and even controversial theory at the time.

In the same year (1609) as Kepler’s findings; Italian astronomer Galileo Galilei (1564 – 1642) became the first person to use a telescope for the observation of the solar system. He observed Mars with more detail than any other human in history, albeit with very primitive equipment. Galileo’s ( at the time controversial) work however prompted many other astronomers to build their own telescopes, and allow themselves to gaze at our red planetary neighbour at closer quarters than anybody before, at a time where the church took a dim view of any discoveries, or attempted discoveries or theories, which were different to their widely accepted beliefs and teachings. Galileo was put under house arrest for his claims that the Earth wasn’t the point of which the other planets revolved around, and it was in fact the sun. Long after his death, and long after his idea of a heliocentric solar system was accepted, the Vatican finally pardoned Galileo in 1992.

The first recorded observations of the Martian surface were made by Dutch astronomer Christiaan Huygens (1629 – 1695). In around 1660, he noted a large dark spot on the surface, blurry and indistinct, yet noticeable. This was later confirmed by far more recent exploration likely to be Syrtis Major Planum- an albedo feature- to the west of an impact basin known as Isidis. Through following this dark spot through the telescope he built himself, he recorded that it returned the same place at roughly the same time the next day. Therefore, Huygens was able to calculate, to his probable astonishment, that the length of a Martian day was almost the same as to an Earth day. This was later accentuated by Italian observer Giovanni Cassini (1625 – 1712), who calculated in 1666 that a Martian day lasted a mere 40 minutes longer than a singular Earth rotation. Huygens, however, was far from finished in his observations of the red planet- and in the early 1670’s he became the first to discover an ice cap at the Martian south pole. He also became one of the first to theorise on the conditions needed for Mars, and other alien worlds, to harbour life- potentially intelligent life- in his work Cosmotheros.

Many astronomers over their next few centuries expanded on the work of Kepler, Galileo and Huygens in observing and recording details of Mars. Many also speculated on the possibility of alien life inhabiting the red planet. Another Italian, Giovanni Schiaparelli (1835 – 1910), recorded what he saw as ‘dark streaks’ zig-zagging down the Martian surface- particularly, he thought, originating from the polar regions. He used the term ‘canali’ to describe these lines and streaks. ‘Canali’ translates in English to ‘channels’, although the similarity to the word ‘canals’ drew widespread attention due to it being mistranslated as such. Especially during a period where the building of canals in England and beyond was popular, the mistaken proposition of canals on Mars lead to ideas of an intelligent race dwelling on the red planet. A popular, yet misguided, hypothesis was that a dying race, living on the dry planet, were desperately building such canals to transport water from the polar ice caps to their cities and abodes around the Martian equator in order to survive. Newspapers of course, latched onto this idea with vigour and even many even advocated humanity try and communicate with the struggling Martians to offer help and assistance, with proposed methods of communication ranging from through the emerging technology of radio waves to the outlandish idea of giant mirrors being used to signal

to the hypothetical Martians. This excitement was soon diminished by later observations by Percival Lowell (1855 – 1916) concluding from his observatory in Arizona that there were no such canals, channels or ‘canali’ on Mars. Interest and even fear of what or who may dwell on the planet was only heightened by the publication of HG Well’s famous novel ‘The War of the Worlds’ (1898) in which advanced, octopus-like creatures with ‘minds immeasurably superior to ours’ land on Horsell Common outside of Woking and, using massive metallic fighting machines armed with a deadly heat ray, wreak havoc in an apparent invasion before ultimately succumbing to earthly bacteria to which they have no defence or immunity.

The latter half of the 19th Century was an exciting time full of new discoveries about our second nearest neighbour. The moons of Mars, the larger, irregular shaped Phobos and the smaller Deimos were discovered in 1877 by American astronomer Asaph Hall (1829-1907). Named after the horses of the Greek God of war- Ares- the Greek counterpart to the Roman God of which Mars got its name- they were and are the first and only known natural satellites of the red planet.

The post-war Space Race began in the late 1950’s between the United States and the Soviet Union, with Mars a key goal for exploration for both superpowers. However, it wasn’t until 1965 where the first high-resolution photographs of Mars and the Martian surface were returned by NASA’s Mariner 4 spacecraft. Before the return of this image, there were even still some lingering ideas and hopes for the discovery of a planet with a rich ecosystem, similar to our own, and perhaps even a civilisation of some sorts. These hopes were quickly dashed, however, when the first black and white images were beamed back to NASA from the spacecraft. They shown a barren, dry and rocky landscape more akin to our Moon than our home planet. There were no cities, no structures, no forests, grasslands or vegetation, and no oceans or seas. After this somewhat of an anticlimax, interest in Mars cooled slightly for a few years as it was apparent the long-held idea of ‘men on Mars’ was all but flattened.

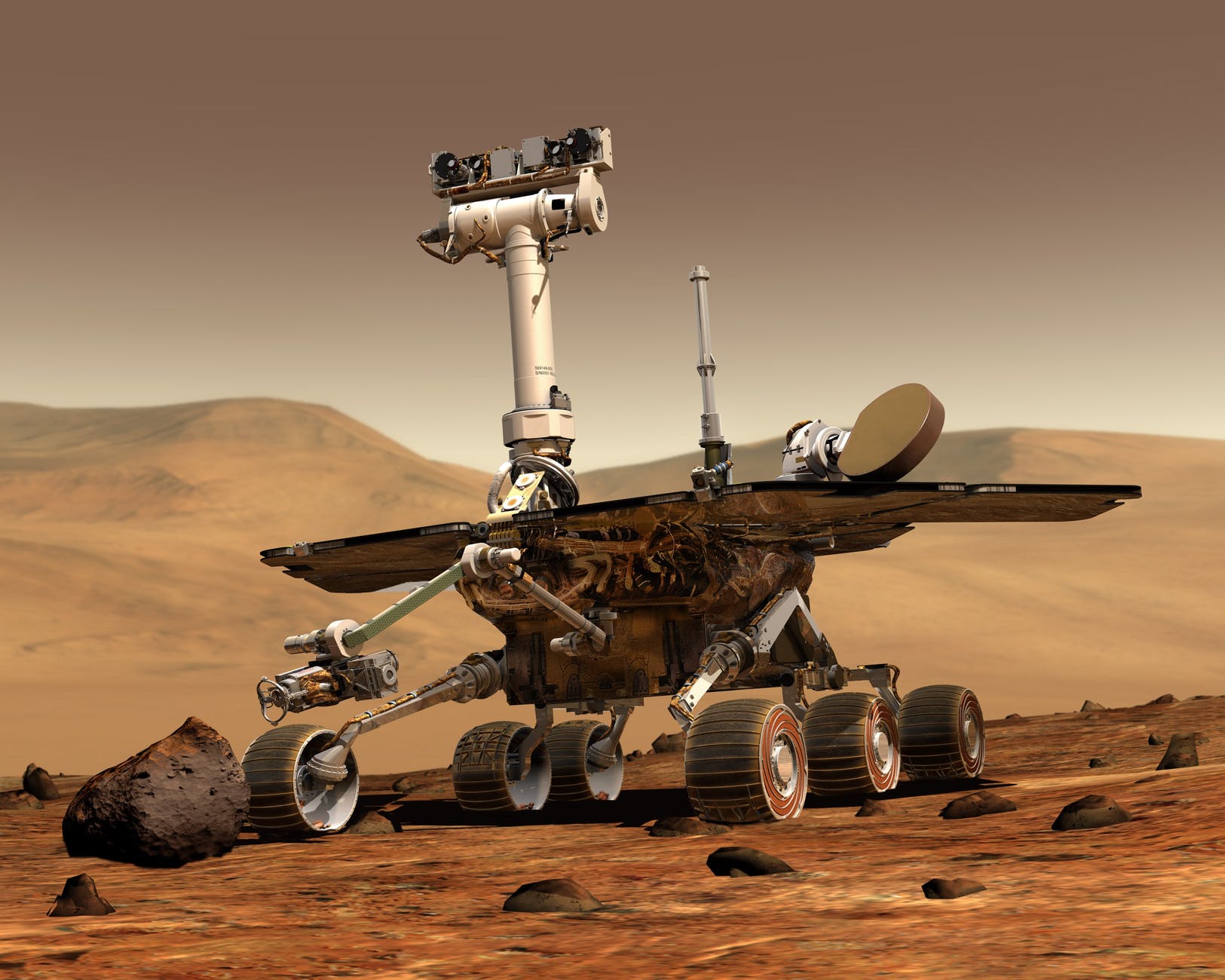

Various more missions to the red planet followed, predominantly orbiters ,with varying levels of success. However, the main mission to well and truly test if Mars was in fact dead or alive took place in 1976. NASA’s Viking landers on the red planet carried an array of scientific equipment and tests designed to monitor and study the Martian atmosphere and surface. One of these tests, the ‘labelled release experiment’, still divides astrobiologists to this day. In this test, tiny samples of Martian soil were collected by the robotic rover and passed into a built-in laboratory. Here, it was put into a vial containing carbon-based compounds (nutrients)- formate, glycine, D-alanine, L-alanine, L-lactate, D-lactate, and glycolate. All nutrients which could hypothetically be consumed and metabolised by a native form of micro-organism. A detector would then wait to see if it could find any traces of waste gases consistent with metabolising micro-organisms, such as Carbon Dioxide (CO2), Carbon Monoxide (CO), Methane (CH4) or Oxygen (O). The test returned an initial positive, albeit with levels of reaction a small fraction of what similar tests would record on Earth, indicating possible metabolising of the nutrients provided. This was a surprise, as previous different experiments had failed to detect even organic compounds- relatively common on other bodies such as asteroids- on the Martian surface. Scientists decided to heat a new sample to a temperature of 160°C in order to sterilise any micro-organisms present. Even more encouragingly; this stopped any reaction taking place, leading to a negative result. This would make sense if the reactions discovered were being produced by micro-organisms. More tests took place, including the storing of a sample at 10°C for several months. This also lead to a negative result. Whilst 10°C for that period of time wouldn’t be deadly to most Earthly micro-organisms; normal surface temperatures on Mars are far lower, averaging around -62°C, therefore prolonged storage at 10°C would be an increase of over 70°C- likely deadly to any Martian micro-organisms. Further tests, heating the sample to 50°C returned a positive- but with a far lower, minuscule level of reaction. Whilst encouraging, these tests have also come under scrutiny, with many claiming Earthly contamination of the samples by bacteria transported on the lander from Earth were to blame for the positive results. It has been proven that spores and hardy microbes (extremophiles) can survive the cold vacuum of space for lengthy periods of time, even though spacecraft, especially those landing on other worlds, are required to be well sterilised due to Planetary Protection regulations.

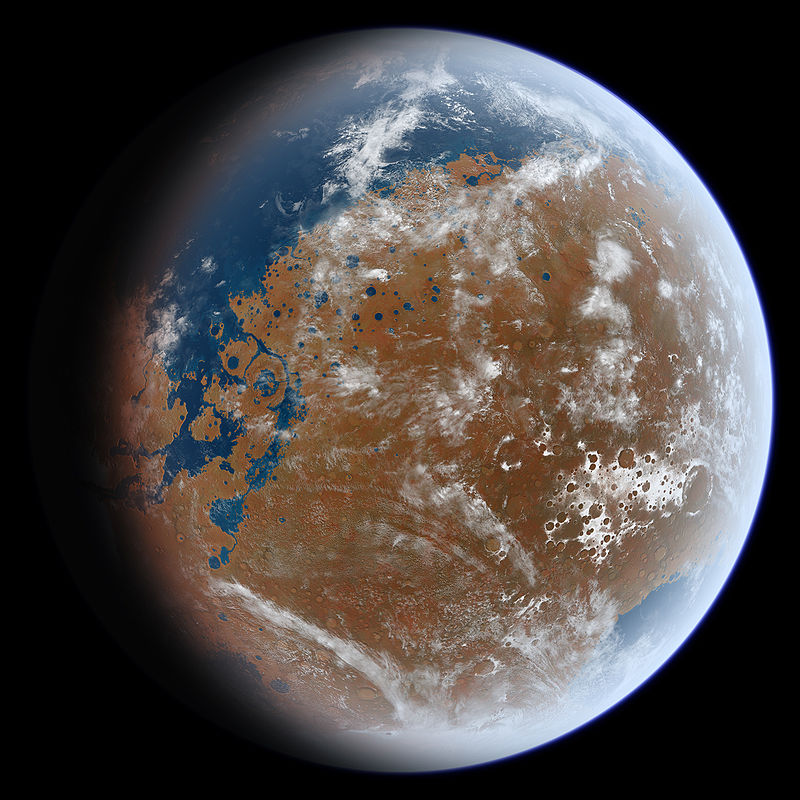

Despite the labelled release experiments of 1976; Mars is still widely regarded as a dead world. Devoid of life and oceans. Although, almost indisputable evidence has been found that Mars in its ancient past was far more Earth-like than it is now, with surface water, oceans and a much thicker atmosphere. Canyons, many vast, have been found which are consistent with being formed by running water. Deposits of salts- similar Epsom Salts- have also been noted, pointing towards ancient rivers and streams. These salts are made of magnesium and sulfuric acid, again elements consistent with the presence of water. Mars likely lost much of its early atmosphere billions of years ago, when it is probable it lost its protective magnetic field, or magnetosphere, due to a cease in the flow of an iron-nickel core like Earth’s, meaning its atmosphere was eventually largely spluttered off into space by the huge and incessant push of the solar wind. Mars’ atmosphere now consists of primarily Carbon Dioxide, with smaller amounts of other elements such as nitrogen and argon, and at the surface the atmospheric pressure is roughly 1% of that at sea level on Earth. NASA orbiters also recently claimed to have discovered streaks of water flowing transiently on the Martian surface. Rich in perchlorates, this water could theoretically survive in a liquid form in the freezing temperatures of Mars, with said Perchlorates acting as a kind of anti-freeze, pushing the freezing temperature of the water far below what it needs to remain in liquid form. However, NASA may have jumped the gun on this announcement, as water cannot exist in a stable liquid form on the surface in the extremely thin atmospheric pressure of Mars. The idea that said streaks were in fact underground and simply seeped through to the surface to become visible is far more plausible. Of course, on Earth water acts as a solvent for life and wherever it is found life, either simple or complex, is also found. this raises the question that if life is or was possible on Mars, despite its toxic soil containing perchlorate compounds unfriendly for life, did life arise and if so is it still there? After all, if life on Earth tells us anything, it is that life is resilient and finds a way to survive, whether it is clinging to an existence around hydrothermal vents deep on the ocean floor (indeed, this could well be where life first had its genesis) or in frozen lakes in the Antarctic. Life finds a way to survive and often thrive in extreme environments. So why not on Mars?

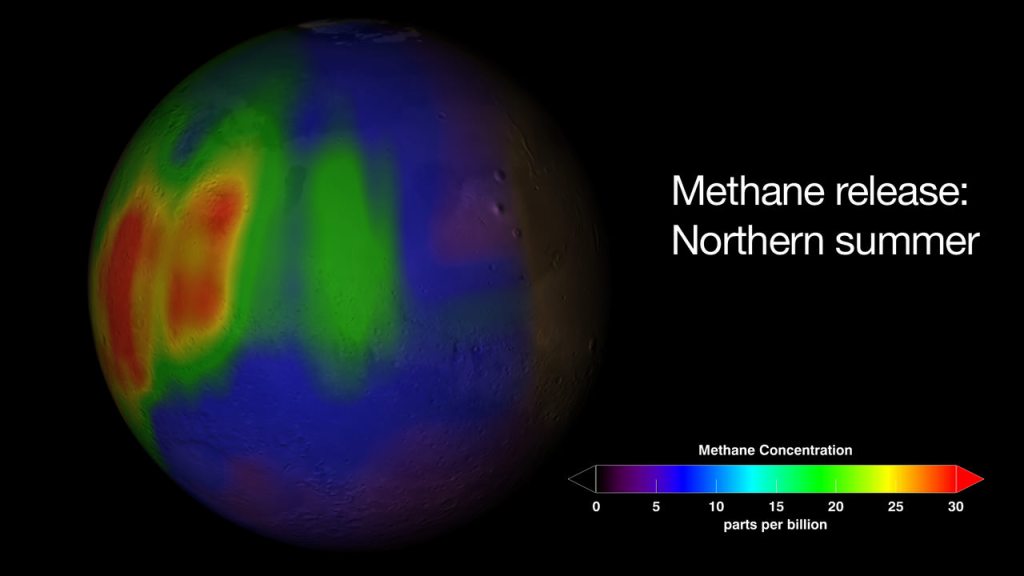

Biosignatures is a term used to describe possible signs of life on another world. Whilst it may seem dead, Mars has teased us with several possible biosignatures of its own. Most famously, or infamously, is the case of the Allan Hills meteorite ALH84001. Discovered in Antarctica in late 1987, microscopic analysis of the interior of the meteorite appears to show tiny structures akin to fossilised bacteria, or nano-bacteria. ALH84001 was likely blown off Mars in an impact of a larger meteorite millions of years ago, with chemical analysis concluding it certainly originated on the red planet. This even lead to US President Bill Clinton later declaring the discovery of extraterrestrial life in 1996, although somewhat prematurely as to this day the structures within ALH84001 are still debated as to whether they are indeed evidence of life and not curious but possible geological processes. Another possible biosignature Mars has displayed is unexplained Methane plumes discovered last decade by NASA’s Martian Curiosity rover. Interestingly, this spikes seem somewhat localised to the Northern hemisphere and also seasonal. A large amount of the of methane produced on Earth is a result of biological processes from animals and micro-organisms. Methane is a bi-product of digestion and metabolism. However, methane can also be produced abiologically through geological means, primarily volcanic activity, so the methane plumes are not necessarily a sign of life. Serpentinisation, a process rare but existent on Earth where layers of hot rock deep beneath the surface of the planet produce methane which seeps through gapes and pores in rocks above is also a possible explanation. Although, Mars seems dormant in terms of volcanic activity, despite possessing the largest known volcano in the solar system- Olympus Mons, so therefore methane -producing micro-organisms are still an option on the table in explaining the peculiar spikes in methane levels. Moreover, methane should not be able to exist long in the Martian atmosphere for a variety of reasons, often related to chemical reactions and low atmospheric pressure, so something must be replenishing it. In late 2019, Curiosity also detected unusually high levels of Oxygen at Gale Crater. This baffled scientists, as there is no easy explanation for these spikes in oxygen levels. At some times, the oxygen levels were higher than expected, and at some times they were lower, signalling a possible culprit is using and/or emitting oxygen. Studies into this are ongoing…

The red planet continues to amaze us, and throw up surprises at every turn. As studies continue, such as the Mars 2020 rover and probable manned missions in the fairly near future, we will surely get a better understanding of Mars and the history, present and future of the red planet. Whether is currently has, or has had life in the past, is a question humanity becomes ever closer to answering. And perhaps the planet come even become a future home, as the idea of terraforming the planet to make it suitable for humans to reside on permanently is not completely unthinkable and is looking more like a feasible idea as opposed to far-fetched science fiction.

In the words of HG Wells; perhaps the future belongs not to us, but to the Martians.