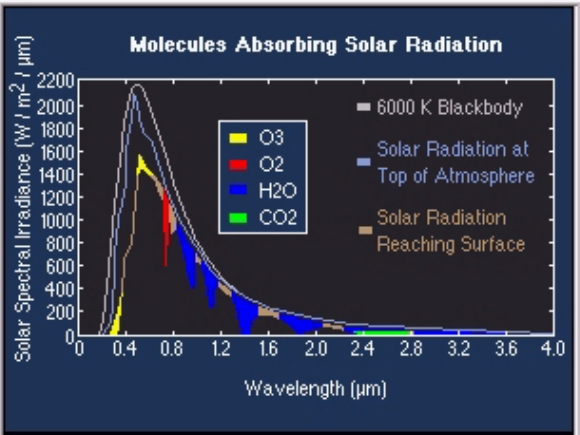

The question of whether life exists on other planets, and whether or not we could detect it if it does, has captivated scientists, astrobiologists and the general public alike for countless years. What many people don’t realise is that this search hasn’t been completely fruitless. NASA have confirmed the existence of life on a planet from space. In December 1990, the Galileo spacecraft turned its various imaging equipment, the near-infrared mapping spectrometer, the ultra-violet spectrometer, the solid state imaging system and the plasma wave spectrometer towards this planet. Using both light reflecting from the planet and light passing through the atmosphere surrounding the planet in a technique known as atmospheric spectroscopy- where slight dips in light and infrared radiation can be analysed to confirm the presence of different elements- the data was able to paint an intriguing picture of the world. High levels of oxygen and methane were recorded, both biosignatures, both in very high thermodynamic equilibrium meaning that their concentrations were so high the likelihood of them being the result of abiological geological processes was extremely unlikely. Other substances such as ozone, nitrogen and carbon dioxide were also detected. Recordings of data in the visible light wavelength were also promising. Large amounts of visible light were being absorbed by the planet, particularly on its landmasses, pointing towards the presence of photosynthesising plants utilising light in the visible part of the spectrum for energy. This would also explain the high levels of oxygen in the atmosphere of the planet. Water vapour in the form of thick, travelling clouds and large, blue oceans and the faint green aura of chlorophyll producing plants could also be seen. The spacecraft observed the dark side of the planet, were the glow of artificial lighting was also noticeable. The albedo and position of the planet in its heliocentric orbit indicated that the surface temperature of the planet was well within the so-called ‘Goldilocks zone’- were water could exist in a liquid form, as well as in a solid form near the poles, and a gaseous form in the atmosphere. As biosignatures go, this planet certainly proved fruitful. Of course, this planet was Earth. The Galileo spacecraft in its flyby of Earth, on its way to Jupiter, recorded this data as an experiment to see if the existence of a biosphere could be seen from space. Whilst we know that life exists on Earth and has an extreme effect on the composition on its atmosphere- this experiment, proposed primarily by renowned astronomer Carl Sagan, served an important purpose. It confirmed it is possible, even easy, to detect the presence of life on a planet from afar through measurements of the light in varying wavelengths passing through the atmosphere of the planet. This would later be used to analyse potential life-harbouring exoplanets. However, detecting biosignatures on alien worlds capable of supporting life through atmospheric spectroscopy is extremely hard with current technology due to the lack of telescopes sensitive enough to detect the light passing through the relatively thin atmospheres of smaller, terrestrial exoplanets. This is liable to change with the launching of new, larger space-based telescopes such as the upcoming James Webb Space telescope. With more sensitive equipment, more detailed analyses can be made of the atmosphere of more Earth-like exoplanets through atmospheric spectroscopy. The imprint these atmospheres have on the light received could be the first tantalising signs of alien life we discover, as if high levels of gases consistent with life (such as methane, oxygen and carbon dioxide) are recorded, especially in notable thermodynamic equilibrium, we can assume with reasonable certainty that life is the cause. Perhaps, although unlikely, we may even discover an exoplanet which as well as displaying prominent biosignatures, contains an atmosphere which imprints upon the light passing through the signs of an advanced civilisation, such as Chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs), Hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs) or Nitrous Oxide (N2O) consistent with an industrial species.

The existence of exoplanets (planets orbiting stars other than our sun) was always speculated but not proven until 1992. Astronomers Aleksander Wolszczan and Dale Frail were studying a pulsar PSR B1257+12, around 2300 light years away, and noticed slight deviations in the tiny fractions of seconds between its pulses. These deviations were also notable because they came at regular, predictable intervals. The explanation given for these deviations was that several large planets in orbit of PSR B1257+12 were responsible for meddling with the pulses of the rapidly rotating pulsar. The likelihood of the planets orbiting the pulsar being viable for life however is very slim to nil. Planets orbiting a star which explodes and becomes a pulsar are likely obliterated or flung out into interstellar space becoming ‘rogue planets’. The worlds orbiting PSR B1257+12 are likely young, protoplanet-like bodies formed when the debris (perhaps a vast mixture of gas, rock, dust and ice) of previous planets destroyed after the star exploded formed a protoplanetary disk and eventually over tens of millions of years or longer, coalesced through gravity into new worlds which settled into a close orbit of the pulsar. The high amounts of radiation given off by the pulsar as it rotates incredibly rapidly emitting extreme pulses of electromagnetic radiation from its magnetic poles, means these planets are likely highly inhospitable to life and are furthermore unlikely to be able to hold on to notable atmospheres, despite their apparent large size.

The discovery of planets around a pulsar in 1992 lead to a push to find planets orbiting a main sequence, sun-like star perhaps more suitable for sustaining life. Throughout the late 1980s and into the 1990s, a new method for discovering exoplanets was developed. Known as the ‘gravitational wobble’ (or sometimes the radial velocity) method, slight shifts in the light of the star could be monitored and attributed to planets in its orbit. When a planet orbits a star, it pulls slightly on it, meaning the star is never stationary if it is being orbited and subsequently tugged upon by one or more planets. These slight movements, or wobbles, are detected by observing the changes in the star’s normal light spectrum. If the star is moving towards us, the light will be shifted slightly to the blue part of the spectrum, if it is moving away, it will be shifted more to the red. If these wobbles occur at regular intervals, it can be established that the cause is orbiting exoplanets tugging on their parent star. A rough estimate of the planet’s size and distance from its parent star can also be made. The first breakthrough in the search for exoplanets orbiting more sun-like stars was made by Didier Queloz, a student at the University of Geneva in early 1995. Using the radial velocity method, he noticed measurements consistent with an orbiting exoplanet around an F-type star known as 51 Pegasi, between 50-60 light years from Earth. Queloz established this world was likely a similar size and mass to Jupiter, probably also a gas giant, but orbited far closer to 51 Pegasi than Jupiter does to the sun, and orbited at an astonishing speed of once every 4 earth days. The discovery of a gas giant in such close proximity to its parent star (and it has now been discovered these are extremely common in the universe) also baffled scientists, as it was previously believed that gas giants generally gravitated to the outer reaches of solar systems, such as in our own.

Whilst the radial velocity/gravitational wobble method was highly successful in the discovery exoplanets, an even more promising and fruitful method later revolutionised the field of exoplanet discovery. The new and now most widely used ‘transit method’ (the vast majority of the 3,000+ known exoplanets have been discovered using this method) consists of observing a star directly for extended periods of time and measuring slight dips in the light curve of the star. These dips are caused by the passing of an exoplanet between the star and the observer. Of course, like the radial velocity method, only a tiny fraction of exoplanets can be discovered as the planetary plane of these stars has to mean that the exoplanets pass directly between the star and the observer, whether that be through ground based observatories or space based telescopes such as Kepler. The presence of an orbiting exoplanet is confirmed when, after a fixed amount of time, the dimming of the light reaching us from the star is observed again. The orbital period of the exoplanet can be determined from repeated observations, with each dimming known as a ‘transit’. The amount a star dims depends on the size of the planet transiting it and the star itself, a larger planet orbiting a smaller star (for example a red dwarf) will produce a more noticeable dimming than a smaller world orbiting for example a red giant. The size of a distant star can be accurately estimated through its spectrum. Therefore, a fairly precise estimate can be made of the size of an exoplanet by measuring the dip in light. However, whilst the transit method is effective for estimating the size of exoplanets, it cannot be used to ascertain the mass. This is where the radial velocity method can assist, as it can be estimate mass. Therefore, in conjunction both methods can lead to an estimate of the density of an exoplanet, and crucially if it is a rocky world or a gas giant.

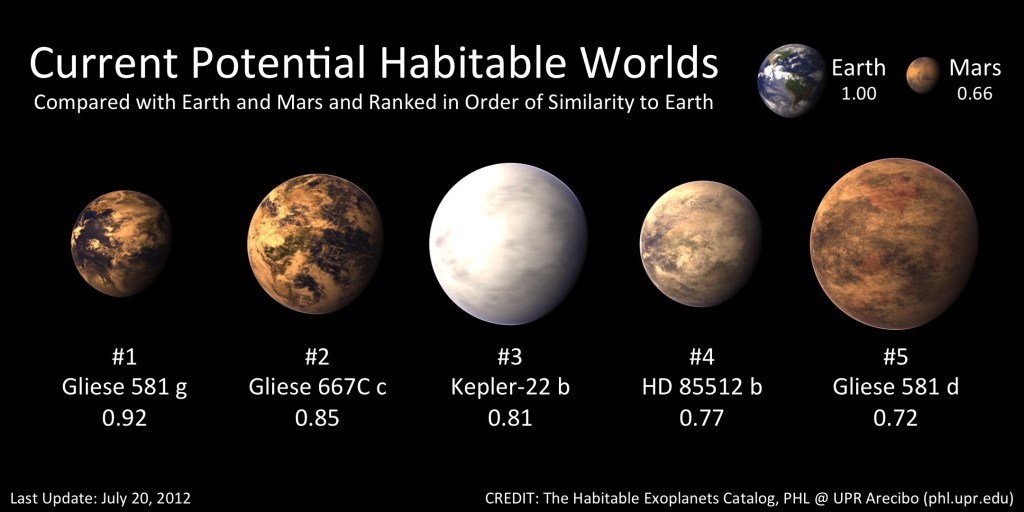

The widely known filter for determining the habitability of a planet is the distance at which it orbits its parents star and whether it is within the so-called ‘Goldilocks zone’- where the surface temperatures on the world are typically sufficient to maintain stable liquid water on the surface. If a planet is too far from its star, water will typically be frozen solid, too close and it will only exist as vapour in the atmosphere (assuming the planet possesses an atmosphere). Whilst theoretically sound, the ‘Goldilocks zone’ or habitable zone theory isn’t necessarily a deal maker or deal breaker for life, as it is based on our experience of Earth alone, as life exists on Earth using water as a solvent. In theory, life could use a different liquid as a solvent for life- such as liquid hydrocarbons on a much colder world. Methane, for example, as been proposed as a possible candidate for being a solvent for life, especially with it being a carbon-based compound and carbon being the building block of all life on Earth. Furthermore, we known from our own solar system that liquid water can exist far outside the habitable zone such as in the so-called ice shell moons of Europa and Enceladus. Protected from solar radiation by a thick ice shell, vast underwater oceans exist here, heated through tidal flexing from their parent planets (Jupiter and Saturn respectively) and perhaps also through geological means, with hydrothermal vents heating the ocean by transferring heat and energy from radioactive decay in the core of the moons (particularly Europa) and into the subsurface ocean.

The habitable zone of a star is directly linked to the size and luminosity of the star. A larger, brighter star will have a larger habitable zone whilst a smaller, dimmer star will have a smaller habitable zone. There is still much debate in the astronomy community as to which type of star is best suited to develop and maintain life. The most common type of star in the Milky Way are the Type-M Red Dwarfs. These also happen to be perhaps the most long lived type of star in the galaxy, with their fuel supplies of primarily hydrogen and helium lasting far beyond the expected 9-10 billion year lifespan of our sun. The smaller the red dwarf, the longer it will continue the nuclear fusion of hydrogen and helium and thus the longer it will live. Smaller red dwarfs may stay in the main sequence phase for trillions of years. It seems counter intuitive for smaller stars to last in the main sequence for such vast periods of time compared to larger stars, but this is simply because they burn through their fuel at a much slower rate compared to much larger stars such as red giants. The longevity and relative stability of red dwarfs during their main sequence phase has made them a potential candidate for harbouring life. Any exoplanets orbiting this type of star has likely had billions of years for which in life to have its genesis, or perhaps to do so in the future. Life on Earth arose almost as soon as the conditions on the planet became habitable, meaning that if life is possible elsewhere in the universe, planets orbiting red dwarf stars have had ample opportunity to develop life, or at least favourable conditions for life to arise in the future. However, many potential barriers for potential life on red dwarf orbiting exoplanets also exist. Firstly, as these stars are relatively small compared to our sun, their habitable zones are far closer in. This can create several problems for potential life. The close proximity of an exoplanet orbiting in the habitable zone of a red dwarf star means it would likely be tidally locked. The gravity of the nearby star would prevent the planet rotating on its axis, meaning it presents the same face to its star at all times (similar to how the moon is tidally locked in its orbit of Earth) thus the planet would be split into two, with one half being bathed in eternal light whilst the other sees nothing but perpetual darkness. It is unclear what exactly this may mean for life however. the planet would not experience night and day, for example. The side facing the star would likely experience extremely high temperatures, whereas the side facing away would exhibit temperatures likely far below zero. Therefore the most habitable area of the planet would likely be around the point where the light side meets the darker side, known as the eternal twilight zone or the terminator. Here, the star would always appear on the horizon and temperatures and light levels would likely be more ideal for life, and shallow water could exist here, as has been proposed on exoplanet Gliese 581G. For life to exist across a whole tidally-locked exoplanet, the extreme temperature differences between the two sides means life would necessitate a substantial atmosphere in order to distribute and regulate temperatures across the planet. Encouragingly, studies in 1997 by Robert Haberle and Manoj Joshi (NASA) proposed that a planet may only require an atmosphere around 10% as thick as that of the Earth to effectively distribute heat from the light side to the dark side, if the atmosphere included greenhouse gases such as carbon dioxide and water vapour. Such a planet, however, would therefore encounter extremely high winds, meaning that any life would have to adapt to constantly high winds, plants would require long, thick roots to anchor them to the ground and animals would have to be large and stocky. Subsurface life could nevertheless survive, shielded from the high winds on the surface. If the planet is part of a binary star system, such as our nearest neighbour Alpha Centauri, additional light could, however, be provided. The low luminosity of red dwarfs also means that any life, particularly plants or plant analogues, would be required to operate at a level of light unfavourable to most Earth life. Most of the (low) light emitted by red dwarfs falls into the infrared part of the spectrum. The low light levels means plant life on orbiting exoplanets would have to be adapted to carry out photosynthesis by absorbing a much wider spectrum of light compared to photosynthesising life on Earth, meaning that they’d likely appear very dark to black if viewed in visible light.

Whilst extremely long lived and relatively stable, Type-M red dwarfs are also quite prone to emitting huge flares. These can increase their luminosity in mere hours, even minutes, this large variation in brightness likely being harmful to any life clinging to an existence on worlds around the star. Such flares would bathe the planet in high levels of deadly ultraviolet (UV) light, which is generally (though not exclusively) harmful to life, after all it is the UV in the light spectrum from the sun which causes sunburn on humans. The close proximity of the planet (orbiting in the habitable zone) to the star emitting these flares also increases the likelihood of the planet being stripped of its atmosphere by highly charged particles, and spluttered into space, and depending on the size of the planet, eroding the atmosphere to almost nil to thinner than before. The fact that it is likely such planets will also be tidally locked is also a factor, as the lack of rotation diminishes the chance of a magnetic field, or magnetosphere, being formed by the planet through the movement of molten metals in its core, thus depriving the atmosphere of protection from charged solar particles. However, a planet receiving high amounts of ultraviolet (UV) light is not necessarily an indication that life is impossible on the world. There are examples of life on Earth which have evolved to utilise ultraviolet (UV) light in a process known as biofluorescence (not to be confused with bioluminescence, which is when a life form is able to utilise chemicals to produce its own light). Certain organisms, most notably some types of coral, exhibit biofluorescence- which is where ultraviolet (UV) light is absorbed at an atomic level and re-emitted at a lower energy level. Essentially, the organism is able to absorb one wavelength of light (such as harmful UV) and radiate it out at a less harmful wavelength such as visible light. Therefore, it is possible that life on exoplanets orbiting close to red dwarfs (or other stars such as larger, younger stars emitting relatively high levels of ultraviolet light) to adapt and evolve to deal with such levels of UV. Moreover, the existence of ultraviolet absorbing life could even be detectable, with more advanced and sensitive equipment, through looking for reactions from exoplanets to solar flares emitted by their parent stars. If an exoplanet is seen to flash, shortly after being hit by an ultraviolet flare, there is a fair possibility that this is due to biofluorescent life absorbing the light from the flare and radiating or re-emitting it in the visible light or perhaps infrared part of the spectrum.

Whilst we do not live in a red dwarf system, there are examples of worlds in our own solar system which could not only harbour life themselves, but could hypothetically have analogues around red dwarf stars which possess a greater chance for life. Ice shell moons such as Europa and Enceladus are relatively common in our own solar system, so the likelihood of them existing around red dwarf stars (the most common type of star) is quite high. This also brings up the possibility of ice shell planets, curiously, no moons outside our solar system, exomoons, have been discovered, although they more than likely exist and will be detected with more advanced equipment by looking for more subtle dips in light before or after the main dip during an exoplanetary transit. These ice shell planets will likely be much larger than the ice shell moons of our solar system and perhaps possess an atmosphere providing an extra layer of protection above the important ice shell which already protects the liquid water subsurface ocean. Another intriguing possibility is that analogues of Titan exist around red dwarf stars. Titan, the second largest moon in the solar system is most notable as it is the only other body than Earth in our solar system to possess stable liquid on its surface. Far out from the sun, it has extensive lakes and rivers, but not of water but in fact hydrocarbons (primarily methane and some ethane). Such worlds, whether they be planets or moons, would be in the outer reaches of such solar systems (like Titan) so any life residing here would be extremely low temparature life. If such analogues of Titan did exist around red dwarf stars, this could be ideal for life to arise, if such low temparature life is possible, and it would have to be methane-based life. Curiously, the (thick) atmopshere of Titan is transparent to infrared light, of which red dwarfs emit abundantly, meaning that more light would reach the surface of these hypothetical worlds than Titan, which is further away from the sun than a likely analogue would be from a red dwarf. This effectively means that there is potentially more than one habitable zone in a red dwarf system.

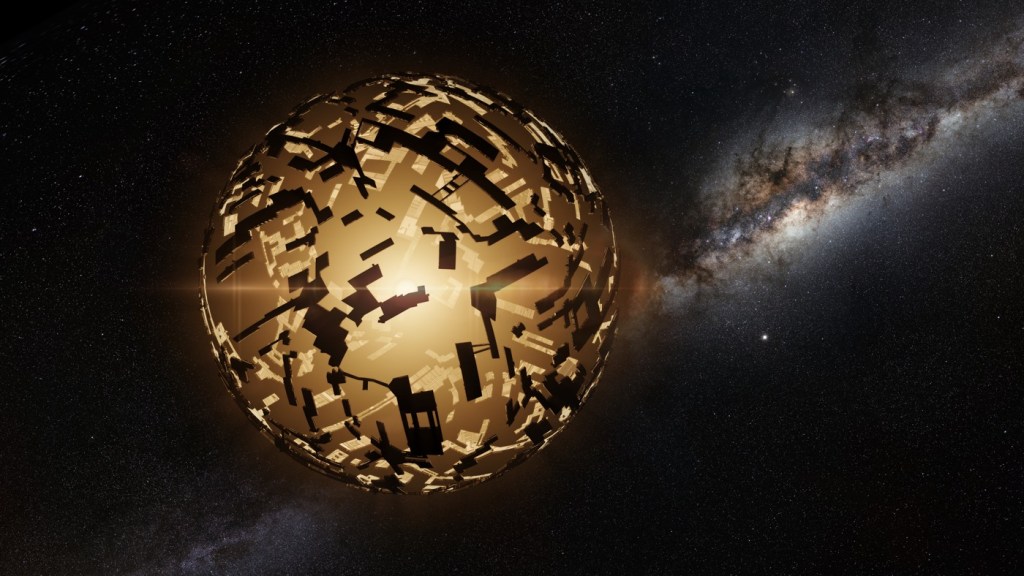

Whilst the potential for life-harbouring worlds around red dwarf stars is still up for debate, one thing that isn’t is the attractiveness of these stars for intergalactic, Type-II Kardashev or above civilisations. The simple fact that these stars last for hundreds of billions, even trillions of years makes them an attractive proposition for energy-hungry civilisations to colonise or otherwise utilise. Encasing a red dwarf in a so-called Dyson Sphere to harness all the energy produced by it would be ideal for an advanced civilisation, as they will continue to provide energy for an incredibly long time. Planets orbiting a red dwarf may also be a huge draw for civilisations looking to establish colonies around stars, perhaps after their parent star has entered its red giant phase or gone supernova. Setting up camp around these stars effectively guarantees countless years of relative safety compared to much larger stars with shorter life spans. An extremely advanced species, probably already experienced in the art of terraforming, could likely also alter any planets to make them more comfortable and viable for life, and could alleviate all the problems that come with red dwarf systems.

The future is encouraging for what humanity may discover lurking around red dwarf systems, and other systems, and with new technology able to perform atmospheric spectroscopy on far off exoplanets the answer to the question “are we alone?” could soon be answered- not through little green men in spaceships or cryptic radio waves emanating from distant constellations, but from the simple imprint an element leaves in light as it passes through a remote atmosphere and into a scientists spectrograph.