Life on Earth demonstrates diversity beyond comprehension. From the simplest, microscopic microbes to gigantic blue whales, from towering Sequoia redwoods to the common garden weed. With such a dazzling array of life, it’s difficult to imagine that there is anything which can transcend the diversity and complexity of all living things to form a common bond. Something all life regardless of size, species, kingdom or genetic make up requires in order to maintain its existence. In truth, there are many substances, such as organic compounds and carbon, which act as a building block for life. However, only one substance holds all the cards for allowing life to arise using it as a solvent: Water. Water (H2O) is the universal solvent of life, as far as we know, as all life on Earth requires it in some form in order to eke out an existence. The ideal solvent for life, the reason water is so useful for life is down to its capability to dissolve a wide variety of different substances; the most of any liquid. The arrangement of the atoms which make up water (H2O) make it a perfect solvent for life, the hydrogen side of a water molecule is positively charged whilst the oxygen side is negatively charged, meaning water molecules are easily attracted to most other molecules. Wherever water exists in nature, it carries within it an abundance of different chemicals, nutrients, organics and minerals- many of which are advantageous or even vital for biology. The importance of water in biochemistry also cannot be understated. Due to its ability to transport dissolved compounds in and out of cell membranes and the fact it maintains various proteins, such as enzymes, vital to life, in their active state- it is no wonder water is the perfect medium for which the vast majority of all biochemical reactions and processes utilise. With this in mind, therefore, it is no surprise that the search for life beyond Earth is typically preceded by the search for water. Particularly liquid water. For a long time it was assumed Earth was the only body in the solar system to possess water in a stable, liquid form. It was also assumed that in order for a celestial object to maintain liquid water it had to be situated within the habitable zone- or the Goldilocks zone. Whilst typically true in the context of surface-based liquid water, recent discoveries have outlined the fact that water in a liquid form can exist well outside the so-called habitable zone, albeit situated subsurface in vast oceans, protected from the cold vacuum of space and the incessant push of solar radiation by a solid crust which makes up the surface of the world. These are known as the ice shell moons, and the two prime examples are Europa and Enceladus- both confirmed to have vast underground reservoirs of stable liquid water.

Discovered in January 1610 by renowned by Italian astronomer Galileo Galilei (1564-1642)- Europa is the smallest of the four so-called Galilean moons orbiting Jupiter (the other three being Io, Callisto and Ganymede). The first spacecraft to pass by Europa was Pioneer 10 in 1973, although too distant to provide clear images of the moon, it was able to detect some variations in the albedo of its surface. The Voyager 1 and 2 missions were able to provide more data on the surface and composition of Europa, which led scientists to hypothesise that the moon contained a large liquid water ocean beneath its icy crust.

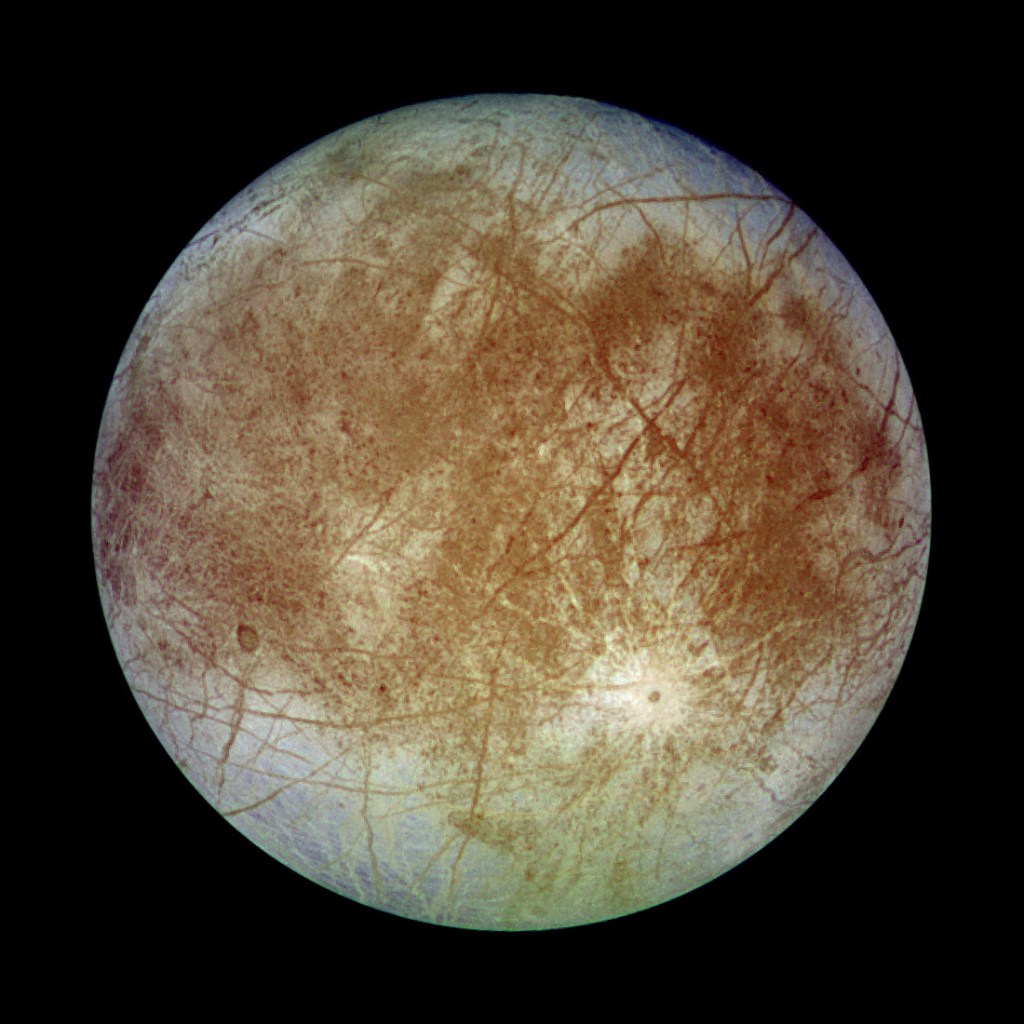

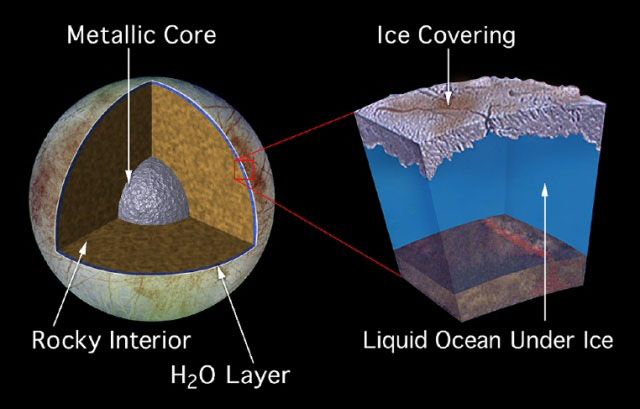

Besides the Galileo spacecraft detecting fluctuations in Europa’s magnetic field indicating a subsurface conductor, likely salty liquid water, the primary clue leading to the conclusion that Europa does indeed possess a large liquid water ocean is the surface. Europa is the smoothest known major celestial body in the solar system, and has relatively little in the way of impact craters, mountains or other geological features. This suggests that the surface, which is far younger than the estimated age of Europa (around 4.5 billion years) is being constantly renewed from below. Layers of ice could be shifting under each other in a similar motion to the subduction of tectonic plates on Earth, indicating a strong likelihood of liquid below. The surface is primarily silicate rock and water-ice, with large cracks visible as albedo features at lower topography, appearing reddish due to minerals such as salts being deposited from the water below which seeped through onto the surface. These minerals are possibly sea salts, discoloured over time by Jupiter’s magnetic field. For the ocean to contain such high concentrations of salts, it must be in direct contact with the rocky surface below. These cracks are also evidence that Europa experiences high levels of tidal flexing as it orbits Jupiter, with the huge gravity of the planet pulling and flexing the surface. Tidal flexing is also likely the primary reason Europa is seemingly able to maintain a liquid water ocean so far outside of the habitable zone. The constant movement and friction generated through tidal flexing from Jupiter’s gravity warms the interior of Europa enough for a liquid water ocean to exist. Europa’s orbital neighbour Io also exerts its own gravitational influence on Europa’s surface, albeit to a less extent than Jupiter, further generating heat in the interior. The icy surface itself is variously estimated in thickness from a kilometre to perhaps tens of kilometres. The total outer layer of Europa which consists of both the subsurface ocean and the hard, icy shell is estimated to be around 100km thick.

As a potential abode for life, Europa is perhaps the prime candidate for producing its own genesis in the solar system besides Earth. Containing more water than in all of Earth’s oceans combined- perhaps double the amount – it is anything but short of the solvent which provides life on Earth the medium for it to carry out the complex biochemistry required for existence. The surface of Europa receives a torrent of radiation from Jupiter in the mega-electron volt (MeV) range, making life on or near the surface highly unlikely. With the protection of a thick ice shell, which Europa has, a subsurface ocean would possibly be reasonably protected from such radiation. This constant pounding of radiation from Jupiter reacts with the ice, which frees Oxygen. Feasibly, this oxygen could make its way slowly into the subsurface ocean- oxygenating it, if the icy shell is thin enough. Alternatively, and perhaps more likely, water pushed up towards the surface through cracks formed through the tidal forces of Jupiter could reach more highly oxygenated areas, and this oxygen could end up in the ocean as the cracks close up. Moreover, the surface of Europa also contains high levels of hydrogen peroxide, which decays into oxygen when in contact with water. Hydrogen peroxide is also important for life on Earth, acting as an energy source which perhaps played a vital role in accelerating the development of life from simple life to more complex, multicellular life.

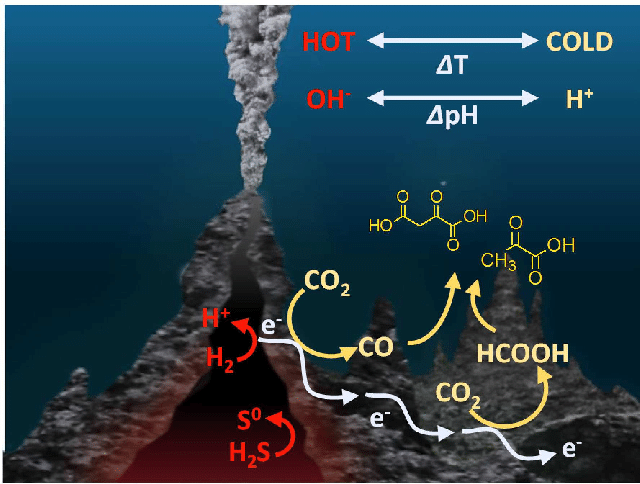

In order for life as we know it to arise, it requires abundant liquid water, the right chemical elements and compounds and an energy source. Whilst Europa possesses abundant water and the correct chemical elements, an energy source has yet to be definitively confirmed. One potential energy source for hypothetical life on Europa is Geothermal energy from tidal flexing. As seen in a much larger scale on Europa’s neighbour Io, this geothermal energy deep in the planet driven through tidal flexing and radioactive decay in the core means that the core of the moon is likely somewhat geologically active. The presence of salts in Europa’s water is a good indication that the ocean is in direct contact with the rocky surface far below. The possible implications of this for life is intriguing. Deep in chasms in Earth’s oceans, heat, energy and chemicals such as sulfides and iron are emitted into the ocean through fissures known as hydrothermal vents. On Earth, these provide an energy source for many organisms, and often host complex and diverse communities and ecosystems of life clinging onto and around them. Like an oasis on the sea floor, the temperatures near a hydrothermal vent can be over 55°C warmer than the mean temperature of waters at the same depth. Indeed, in the 1980s scientist Gunter Wachtershauser proposed in his iron-sulfur world hypothesis that life on Earth first had its genesis around hydrothermal vents, meaning that if this is the case, if they are present on Europa there is every chance life could also have arose deep in its ocean, and may still eke out a living around them. These could be simple single-celled organisms which use the hydrogen sulfide emitted by the vents as an energy source.

Another potential habitat for hypothetical life on Europa is far above the mineral rich deep ocean floor at the bottom of the ice shell itself. Beneath ice sheets in Antarctica, life can thrive at the point where the ice meets the water using the energy gradient produced by the melting and refreezing of the ice to power metabolism. This melting and freezing of the ice on Europa does likely take place, due to tidal flexing from Jupiter’s intense gravity. Such life, or traces of, could even be detected through spectroscopic analysis of plumes being ejected from Europa’s surface- which have been recently detected by the Hubble space telescope.

Whilst a definitive answer to whether or not Europa is an abode for life would likely only be reached with the exploration or analysis of its ocean water, studies of the surface of the world have also thrown up a possible lead in the search for life. The peculiar red staining around the cracks, or linea, on Europa’s surface has lead to speculation that microbes deep below or perhaps frozen in the ice are the cause. Whilst some maintain it is simply the result of the discolouration of salts and minerals by Jupiter’s magnetosphere, it is still unclear what chemical processes could cause this. In 2002, planetary geologist Brad Dalton of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) looked at this red staining in the infrared and compared it to the infrared signature of photosynthetic algae that lives around hot water springs in the Yellowstone National Park here on Earth. The infrared signatures of both the red staining on Europa and the algae were surprisingly similar. In addition, Dalton took a variety of other microorganisms and subjected them to Europa-like conditions, and found that their infrared signatures were loosely similar to Europa’s red staining. The infrared spectra obtained of Europa by the Galileo spacecraft did show that these areas consisted of water ice bound to another material. This could well be salts such as or similar to Epsom salts, although these typically appear white- and do so on Enceladus- so the red colouration is unusual, if indeed the hypothesis of the discolouration being caused by Jupiter’s magnetic field turns out to be false. Moreover, no mix of salts exists that are a precise match to the infrared signatures seen from the stained areas on Europa. Another potential explanation is that the staining has been caused by different sulfur compounds, perhaps again being the chemical product of radiation from Jupiter hitting the surface of Europa. A possible explanation for such sulfur compounds being present on the surface of Europa is its sister moon, Io. Io is wildly volcanic, and spews sulfur out into space incessantly, and there is evidence that some of this sulfur has collected on the surface of Europa. The way in which both planets orbit, and the fact Jupiter rotates rapidly, far faster than Europa orbits, means the majority of Io’s jettisoned sulfur settles on the trailing side of Europa- Europa being tidally locked to Jupiter, eternally presenting the safe face to the planet akin to Earth’s moon due to gravity. The proposal that deposited sulfur compounds from the volcanoes of Io are responsible for the staining on Europa does make sense, however, it does not explain why the staining is almost exclusively situated on and around the cracks in the surface. This clearly shows that the staining is directly related to the cracks, and it seems beyond unlikely that sulfur deposits from Io would collect around the cracks and almost nowhere else. Although the infrared spectra of the cracks resembled that of biology on Earth, it wasn’t a perfect match. However, Dalton also noted that the difference in the spectra of two bands in the Earthly bacteria correspond with amide bonds in the protein coatings of their cells. Amide bonds are essentially the link that bind or hold proteins together, and without them you just have amino acids which are commonly found abiologically in space, particularly on asteroids. Although this could explain why the infrared spectra of the Europa colouration isn’t an exact match to bacteria in similar conditions on Earth, even if it is indeed frozen microorganisms responsible for the staining on Europa’s cracks, Dalton also proposed amide bonds could be broken on Europa’s surface due to high levels of radiation, and if those bonds are put back together in a stronger form then their infrared spectra could more closely resemble the Europa data. Dalton does also note that amide bonds are strong, and even in the highly radioactive environment of Europa’s surface may remain unbroken, although amide bonds absorb ultraviolet light (UV) at 205 nanometre wavelengths, and this from the sun in conjunction with radiation from Jupiter could possibly cause the bonds to break. Whilst far from definitive proof of microbial life, Dalton’s findings do remain on the table as far as evidence for life on Europa is concerned. Some scientists have even proposed that they would be surprised if Europa doesn’t harbour life, and that if it does, it could even be more than microbial.

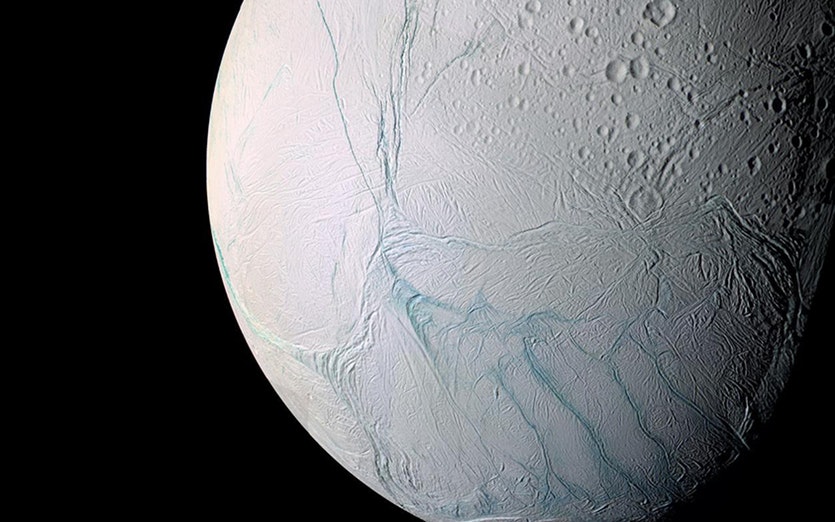

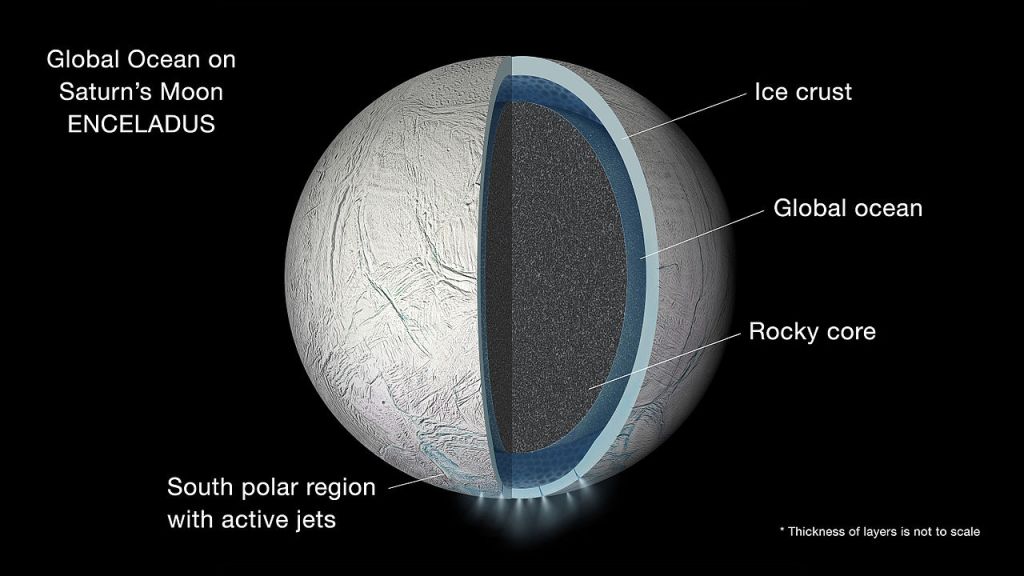

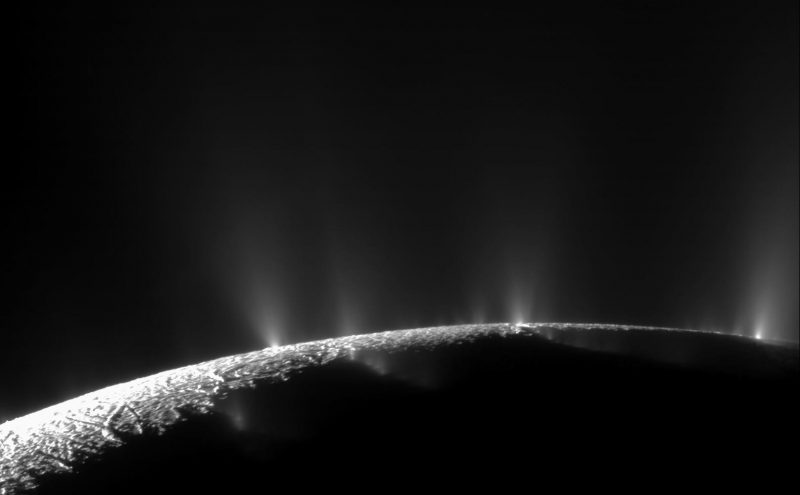

Discovered in August 1789 by British astronomer William Herschel (1739-1822), Enceladus is the sixth largest moon of Saturn. Although small, it is one of the most intriguing bodies in the solar system in regards for the search for liquid water and subsequently alien life. Enceladus can be described as almost a ‘love child’ of Jupiter’s Galilean moons Europa and Io- as it is an ice shell moon, very much like the former, but also possesses volcanoes which also grants it some similarity with Io. These volcanoes however, are not the same as those found on Io and indeed on Earth, they are in fact cryovolanoes- erupting not molten rock and metallic elements but instead icy water in vast plumes. This water falls as snow across the entire moon, making the surface a glistening white with a blueish tint, and causing Enceladus to have one of the highest albedo’s of any solar system body. These watery plumes were discovered in 2005 by NASA’s Cassini spacecraft, and were found to be emanating primarily from the southern hemisphere of the moon. Whilst much of the material from these cryovolcanoes falls back onto Enceladus as snow, a large amount is also jettisoned into space and actually forms Saturn’s E-Ring. The presence of these plumes is cited as very strong evidence that Enceladus, like Europa, has a vast underground ocean of liquid water- heated by a combination of tidal flexing from Saturn and radioactive decay deep in the moon’s rocky core.

In 2017, NASA’s Cassini used its mass spectrometer to more closely study the chemical composition of the plumes of water coming from Enceladus’ southern hemisphere. Previously in 2005, similar tests had discovered that these plumes were indeed water, consisting of water vapour and hail/snow-like chips of ice as well as Carbon Dioxide, Methane and simple organic compounds. The later mass spectrometer tests discovered hydrogen in the plumes. This is encouraging in terms of determining the potential habitability of the ocean, where it is strongly believed these plumes originate. Hydrogen can be used as an energy source by microscopic life, who can combine carbon dioxide dissolved in water (CO2 is present in the plumes) in a process known as methanogenesis- and this term is used as the by-product of this process is methane, which is also present in the plumes, as well as ammonia (also present) which is a by-product of protein metabolism. The presence of hydrogen also suggests that the ocean may be reacting with heated rocks deep on its floor. This could be through geothermal vents on the ocean floor, known as ‘white smokers’ on Earth. This provide sustenance for life, simple and complex, and are surrounded by rich ecosystems on Earth. Many simple and some more complex organic compounds, such as macromolecular organic compounds, were detected by Cassini, and it is likely that even more complex organics are present as well as other yet-to-be-detected substances important for life such as sulphur and phosphorous . The detection of these simple organic compounds, as well as the other substances friendly to life, doesn’t confirm that life exists on Enceladus, only that the building blocks of life are largely present in the ocean of Enceladus. There’s also evidence that the ocean is significantly warmer in the southern hemisphere of Enceladus, meaning the moon may well be quite ideal for hosting life. In fact, some recent studies have concluded that Earthly bacteria known as methanogenic archaea could be quite well suited for life in the conditions around Enceladus’ hydrothermal vents. These, through methanogenesis, use molecular hydrogen and carbon dioxide to produce methane (all three are abundant in the moons ocean). Moreover, the geological process which produces Enceladus’ molecular hydrogen- serpentinisation of olivine- could well produce enough molecular hydrogen to support such microbes in the ocean. If such a microbe is living on Enceladus, it could potentially be the source of the methane detected by the Cassini spacecraft. However, methane can also be produced through abiological geological means and released into the ocean through hydrothermal vents, so a conclusion of methanogenic life is not a certainty.

Standing against Enceladus potentially being inhabited by alien life is its age. It is estimated to be only around 100 million years old- which is extremely young in cosmic terms. Although the exact age of Enceladus isn’t definitively known, it is thought to be this young and the relative smoothness of its surface could be evidence of this youthfulness. Enceladus simply may not have been around long enough for life to arise, despite it generally exhibiting factors which make it quite favourable for life. However, whilst the exact details and time scale of the genesis of life on Earth aren’t known with absolute certainty, it does seem that when conditions on Earth became favourable for life, it arose fairly quickly. Also, organic chemical reactions do generally occur very rapidly, so the apparent youthfulness of Enceladus doesn’t completely rule out the possibility of life on the tiny world. Even if it is too young to harbour life now, the seemingly favourable conditions mean that perhaps in the future Enceladus could be a laboratory of sorts, where humanity in the distant future could observe and study the genesis of life on another world in an amazing and unique opportunity. When the sun enters its red giant phase in approximately 6 billion years, the habitable zone of the solar system will also move further our into the outer solar system, so perhaps Enceladus could have a few hundred million years of existence as a water world, bustling with life, as its outer shell melts and forms a vast ocean that spreads from pole to pole.

Whilst the ice shell moons of Europa and Enceladus aren’t the only other bodies in the solar system to contain liquid water, many other moons as well as Pluto and other Kuiper belt objects are thought to also possess subsurface oceans or lakes, they have broadened our horizons in the search for life so we now look beyond the traditional goldilocks zone. Perhaps in other solar systems, ice shell planets with unimaginable amounts of liquid water exist, further providing a potential abode for alien life using the same universal solvent as all life on Earth does: water. Hopefully, one day, proposals to send a probe under the veil of ice covering Europa get the go ahead, and we might finally get the answer we are looking for in the search for alien life.